by Justin Marquis

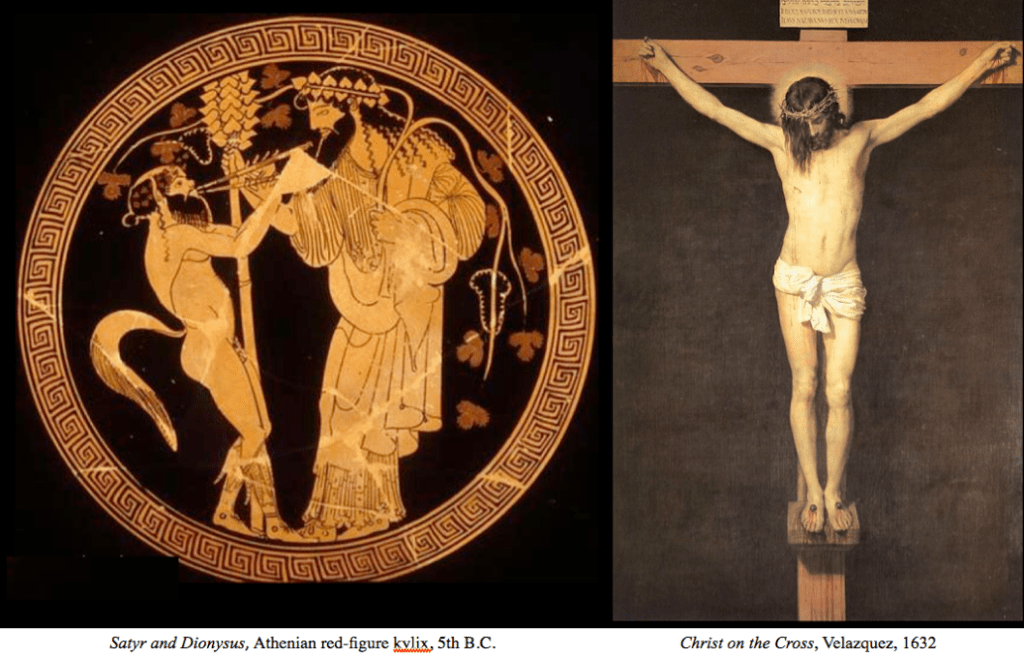

A Nietzsche scholar in seminary, a Christian writing a blog invoking the pagan God of wine; what exactly is going on? Nietzsche himself proposed a dynamic and even violent opposition, expressed as Dionysus versus the Crucified, between the God of wine and Christianity. Dionysus the god of subterranean, sometimes violent urges, the god of intoxication, trances, of that which rumbles below reason and which reason cannot express. Dionysus represents that which ultimately cannot be represented, that which defies reason, that which cannot be seen in images or expressed in words but which is felt in the beat of the drum and the rhythm of the dance. What does such a god, an idol of the pagan Roman, Greek, and Eastern Mediterranean world, have to do with Jesus, God the Son, the crucified one?

Nietzsche uses the god Dionysus to stand for a side of human experience, a side that reason cannot express and that transgresses traditional social boundaries. It is the chaos of the ecstatic, the shaman, and the drunken reveler. Nietzsche argues that part of what made Greek civilization—and by extension Western Civilization—great was its ability to express the Dionysian side of human experience without letting go of rationality, knowledge, order, and social tradition. These two, seemingly opposed sides of what it is to be human, are necessary for a healthy, full, and creatively productive life and society.

Whereas Nietzsche lauds the Greeks for embracing the Dionysian despite the tension and pain its existence can cause, he criticizes and finally rejects Christianity for its seeming inability to hold this same tension. Christianity, Nietzsche argues, opposes the Dionysian in favor of making all things knowable, all things rational, denigrating the pre-rational urges and desires that make up the chaotic subterranean nature below our conscious thought with its rationality, morality, and adherence to social cohesion.

One of my starting premises is that Nietzsche is indeed right, a full human life and a healthy human society need to express and create out of both their Dionysian urges and ecstatic revelries, as well as their coherent and comprehensible rationality. The tension and interaction between these two sides of human nature is fertile for artistic creation and philosophical discovery. Denying one of them is to deny a part of what makes us who we are. Where I depart from Nietzsche is in his evaluation of Christianity. A second principle I work from is that Christianity cannot be evaluated as a whole because Christianity, as such, does not exist. There are multiple Christianities that, while all naming Jesus as their focal point, are only superficially similar to one another. Once we acknowledge that Christianity is multiple things, it is possible to see Nietzsche’s critique not directed at Christianity as a whole but at certain expressions of it.

Nietzsche, in one of the last things he wrote, opposes Dionysus, God of overflowing life on the one hand, to the Crucified on the other. Opposing a religion Nietzsche saw as dour, life-denying, obsessed with the afterlife and a magical understanding of the unfolding of history, Nietzsche favored a God who could dance, a God whose lust for life extended to the Dionysian side of human life. Nietzsche was correct that a Christianity that only focuses on the crucifixion is life denying and misses a whole other side to human experience. For a complete and whole Christianity, one must add to the crucified, the risen one, a God who dances, a God who turned water into wine, a God who broke bread and ate and drank and whose lust for life was so strong that the grave could not contain him.

It is a common error to think that the Christian is forbidden from acknowledging the pagan gods. What the Christian is forbidden is to sacrifice to the gods. The Christian does not worship Dionysus, but the Christian can joyfully acknowledge that he exists. Dionysus understood as a personification of whole half of human nature and experience must be an aspect of the deity who took on human form. Jesus Christ, the crucified and risen one, twice born one, celebrator of festivals, the God-Man is a God who dances, a God of the chaotic, the subversive, the subterranean, and the hidden. Only a Christianity that celebrates this side of what it is to be human and this side of what it is to be divine is capable of affirming life and loving people and God in their fullness. I, along with Nietzsche, reject any church, creed, or confession that denigrates life and holds up only the crucified without also embracing the Risen One.

Leave a comment